Things are great this morning. I have a ton to blog about and a long list of "good" chores. God, I'm happy that February is done. Which is a weird way to lead up to this story.

Things are great this morning. I have a ton to blog about and a long list of "good" chores. God, I'm happy that February is done. Which is a weird way to lead up to this story.

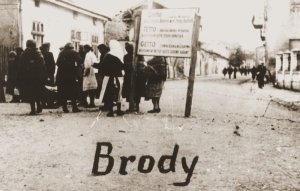

The New York Times reports that researchers have finally counted up the number of death camps, slave labor centers, ghettos, and brothels that existed in Nazi Germany. The number? 42,500.

Why didn't anybody properly document these numbers before?

This number is important for a lot of reasons. First, it shows that nobody in Germany could honestly claim that they didn't realize that Nazi were killing Jews. Second, it helps survivors and their relatives in court. Third, it shows how much resources the Germans devoted towards genocide. Could they have won the war, if they hadn't been so hell-bent on killing people? Fourth, numbers are important. It gives a way of conceptualizing the horror.

The Times put this article online on Friday and we've been talking about it for four days.

My mom and her best friend would call each other every March 1 to wish each other a happy March 1. My mom hates February. Which is weird because her eldest was born in February. Maybe it’s the recurring nightmare of the last 24 days of her first pregnancy that haunts her.

Has anyone seen a good map or list of where the death camps were? I could only find one with vague dots.

LikeLike

“Could they have won the war, if they hadn’t been so hell-bent on killing people?”

Here’s a problem with that statement.

Gotz Aly argues in “Hitler’s Beneficiaries” that loot was a leading motivation for the Nazi military project–the Nazi economic regime was a disaster and the German standard of living would have collapsed without Ukrainian eggs, French cheeses, Norwegian herring, the property of deported Jews, etc. Aly argues furthermore that the genocide was driven by the looting–the Germans needed to make sure that the owners of the stolen property did not return to claim their stuff. Note that this tracks with the fact that genocide was a fairly late addition to the Nazi project.

Sure, they might have been able to win the war if they had been less distracted by genocide, but the war was not an aim in itself.

LikeLike

Also, a big part of many of the camps was forced labor (i.e. slavery), until the costs of feeding the labor force exceeded the value of the labor. The story of the holocaust survivor who was at 5 different camps illustrates that transition. He was successively transferred to places where his forced labor would be useful until he was eventually killed.

I like to think there was no way that Germany could have won that war, but I know that’s too simplistic a position to take.

LikeLike

I am always troubled by descriptions of the holocaust that concentrate on either the Nazi’s evil or, sometimes, though rarely, on the general evil of Germans.

Personally, I am haunted by the bystanders, and because I think there are lots of human behaviors that lead to our being bystanders to evil (even while being fairly confident that many of us are not inclined to evil ourselves).

LikeLike

“I like to think there was no way that Germany could have won that war, but I know that’s too simplistic a position to take.”

Once Germany invades Russia, it’s a matter of time and how many casualties on the Russian side. Even if the German army takes Moscow (as Napoleon did in 1812) there’s no faction to make a Brest-Litovsk peace. American entry into the European theater (Soviet troops loved Studebaker trucks), and Allied unity make the Nazi loss faster, but I don’t think there’s a scenario that ends with stalemate in the east. Given that the Red Army inflicted 75% (or more, I forget the exact percentage) of the Wehrmacht’s casualties, sooner or later the war in Europe ends with Soviet soldiers in Berlin.

LikeLike

but I don’t think there’s a scenario that ends with stalemate in the east.

There wasn’t for the Nazi’s. Somebody who didn’t regard Slavs as subhuman may have been able to capitalize on the difference between Russian and Soviet.

LikeLike

Somebody who didn’t regard Slavs as subhuman may have been able to capitalize on the difference between Russian and Soviet.

Or, more to the point, between Polish and Russian. And so again, the main choice is not invading Russia.

Stauffenberg’s plot is too little, too late. An army-led, non-Nazi government might have tried to return to the pre-Barbarossa border in the east, but by July 1944 the Western Allies have opened the second front, and Stalin doesn’t have any need to buy what the German army would be offering.

I don’t think bj’s take is simplistic at all; once the German political leadership decides to invade Russia, the war is lost. Not instantly, or even quickly, but eventually and inevitably. (Ok, as much as one can actually talk about inevitability in history.)

LikeLike

It makes me sick to my stomach.

It would be nice to live in a world where I don’t have to apologize or feel guilty for being German all the time. I agonize over the thought whether I would have had to courage to protest, like Sophie Scholl. Every German girl who learns about her in school has these thoughts. Many like to think of themselves as potential Sophies. My worldview is a bit dimmer.

It’s interesting, though, that people I meet from other nations (and I meet a lot) have no doubt about the fact that they would have stood up. Like those people who were for the second Iraq war. Or so.

As I said, my view on these matters is a bit dark.

(I caused a huge scandal in my husband’s family when I dared to doubt the wisdom of re-electing Bush and excusing torture. I told them I thought torture is a very slippery slope. I was told that as a German, I had no right to say that. I answered that exactly because I’m German, and I know my history, and I know how very slippery those moral slopes are, I can say this. After some weeks I had to apologize, just to make peace.)

LikeLike

Or, more to the point, between Polish and Russian. And so again, the main choice is not invading Russia.

Not exactly what I was thinking. Roughly speaking, I was envisioning an alternative history where the German plan was “Give guns and bread to the Ukrainians*.” Still a long shot, but more likely to win than the actual plan and more likely to happen than getting Polish troops involved with the Germans given that the Germans invaded Poland before the USSR did.

* and similar SSR’s.

LikeLike

Conceivably a Germany which managed to ally with Eastern Europe against Stalin could have won the war even with the Eastern Front, but that would have relied on Germans not being Nazis. Given less alternate reality, even if the Nazis had won in that they militarily defeated Russia, there’s no way they could have actually achieved their goals, since occupying hostile lands and mass murder are difficult, demoralizing, and resource intensive, and the planned extermination of almost all Slavs would have involved both.

The question of whether the Holocaust cost Germany victory is hard to answer because it’s hard to know the causal link–did the Germans start losing because they devoted more resources to genocide, or did they start focusing on genocide when it became more and more apparent they were losing the war? The answer doesn’t have to be one or the other, but it’s pretty clear at some point Nazi leadership gave up on trying to win and turned their attention solely to killing all of Europe’s Jews.

ExpatMom,

Yeah, the pervasive idea that we’d be heros in that situation really annoys me, first off because we really probably wouldn’t and thinking we would involves incredible self aggrandizement, and secondly because we already have failed on that level given current human rights abuses. This can be a huge problem with how the holocaust/WW2 is often taught in the US, where becomes “good vs. evil rah rah rah we’re the goodies” rather than a chance to reflect on how it comes to happen that people who are not intrinsically evil or bad can end up collectively doing really terrible things. We have some family friends whose parents & grandparents did stand up to Hitler, even at great personal cost. One father who spent the war smuggling Jews out of Germany told his son not to see him as a hero, because, as he pointed out, by the time you need individual acts of heroism, you’ve already failed on a societal level to prevent evil from taking place.

LikeLike

“There wasn’t for the Nazi’s. Somebody who didn’t regard Slavs as subhuman may have been able to capitalize on the difference between Russian and Soviet.”

Right. There were a lot of elements in Eastern European who would have loved to fight the Soviets, for instance, the Ukrainians.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrey_Vlasov

However, the Nazis were way more interested in looting Ukraine than liberating the Ukraine, so they poisoned that well. There were, however, still non-Germans willing to fight under the Nazis (for instance under Andrei Vlasov). The Soviets deemed getting taken prisoner a criminal offense, deserving of a sentence of 10 years in the GULAG, so Soviet prisoners of war were a recruitment pool for the Nazis. Soviet POWs had very little to lose by fighting the Soviet Union. Stalin had also just purged his officer corps before WWII broke out. Adding up all of those things, the Soviets did have a lot of soft spots, but the Nazis were not ideologically well-positioned to exploit them.

(Here’s a bio of Vlasov, the leader of the “Vlasov men” who fought under the Nazis.)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrey_Vlasov

MH said:

“Not exactly what I was thinking. Roughly speaking, I was envisioning an alternative history where the German plan was “Give guns and bread to the Ukrainians*.”

If the Nazis had been the sort of people to do that, they wouldn’t have been Nazis.

LikeLike

Expat Mom, I poked around and see you live only an hour or so from my German relatives (southern Thuringia). Cool!

When we visited them, we saw lots of old family photos, and it was really hard to realize, looking at photos of my cousin Dietrich’s father in his German army uniform, that my grandfather fought in WW2 for the US against his father’s first cousin in Germany. My grandfather survived; Dietrich’s father didn’t. When we looked at the photos, I didn’t talk about that as I didn’t want to raise the issue of the Nazis. We spent some time where the border was, talking about life in East Germany, though, under communist rule.

I suspect some other cousins were Nazi politicians, but I haven’t been able to connect with that part of the family (I connected with this branch by simply sending a letter to everyone with their last name in the town where my great-great-grandfather was born). My suspicion is that this branch ended up over the border into Bavaria.

LikeLike

“Yeah, the pervasive idea that we’d be heros in that situation really annoys me, first off because we really probably wouldn’t and thinking we would involves incredible self aggrandizement.”

I’ve read a lot of memoirs of life under Mao and Stalin, and under those circumstances, even very small, ordinary things (like keeping family photographs) require heroism. Under Stalin, not denouncing and divorcing an arrested spouse would require enormous courage and sacrifice. (And in fact, given the danger that would pose to your innocent children, it wouldn’t be at all an easy moral call.)

Life under the Nazis was probably somewhat different, but under Stalin or Mao, it was a rather substantial moral achievement just not to betray your family and friends, to preserve your own basic humanity. (I’m not sure what the equivalent would have been as a German under Hitler–not accepting gifts of looted butter or shoes?) There’s a very good Chinese movie about the Mao era called “To Live” that I think illustrates how difficult it is to live an ordinary life under totalitarianism, and what an achievement it is.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_Live_(film)

Solzhenitsyn also talks about not participating in the lie.

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/augustine/arch/solzhenitsyn/livenotbylies.html

(He wrote that in the 1970s, so the stakes were substantially lower at that point.)

LikeLike

It occurs to me that even just not taking advantage of certain opportunities might be heroic.

My husband’s family is from Poland, but rather ethnically mixed (German, Jewish, etc.) as is normal for that part of the world. My MIL’s maiden name is German. Anyway, under Nazi occupation, locals with German ancestry (Volksdeutsche) were very advantageously positioned to collaborate with the Nazis and help loot their native countries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volksdeutsche

There was a great-uncle who wound up flying a bomber in the Luftwaffe (he claimed he tried not to hit anything), but he was apparently the only member of the family to go over to the Nazis.

LikeLike

B.I., here’s a view from a history of the Polish-Soviet War, which covered much of the same ground 20 years earlier:

In that war, the Polish army “ran all the way to Kiev, and ran all the way back.” (Wikipedia has 14 articles in the category “Polish-Russian Wars,” so it’s not as if people haven’t kept trying.) But Germany can’t conquer Russia; it can’t occupy the conquered parts; and the specific regime can’t offer the subject peoples what it would take to split the Soviet Union. Once Barbarossa launches, the regime’s fate is sealed, even though that’s in no way clear to anyone at the time.

As for a causal link between the war effort and genocide, I’d be open to arguments but my general sense is that the two state objectives ran mostly on parallel tracks. There was support in both directions, of course: slave labor for the war effort, and who cares what happens to those workers; army units involved in both transport and massacre. I’m not precisely sure where it nets out, but I think the resources devoted to massacring civilians are not sufficient to have changed the outcome of the fighting.

LikeLike

My maternal grandfather had to flee Berlin at dawn, escaping the death squad sent out to get him. Opposition to Hitler was dangerous. Not sure about the other side of the family. Lots of silence there. When I was very young, I asked my grandmother and she told me that they weren’t Nazis. Hard-headed Lutheran that she was, I can see it – almost. But then she was a group leader in the Hitlerjugend. German past is painful and in the meantime, pretty much everyone has died.. I can only hope we have learned something.

Wendy, if you ever get back to Germany, come and see us! The US economic crisis stranded us here – and with every passing day, I’m wondering whether that may be a blessing in disguise… (Husband is US working in the AID business – not the best career to have at the moment)

LikeLike

Now that I’ve finally read all of the article, I’m also going to go with “not all that shocking” on the main thesis.

Slave labor was pervasive in Nazi Germany and occupied Europe. By defining as a camp every place where forced laborers lived, the study comes up with a very large number. But it’s not like there were 40,000 Treblinkas scattered across Nazi-controlled parts of Europe. And forced laborers probably aroused about as much comment as men in orange jumpsuits picking up trash on the side of the highway.

LikeLike